Every spring I take great joy in watching the blue herons nest in a grove of tall trees not far from our home. There are over a dozen huge nests in the heights of the bare branches. The mothers are clearly visible as they sit patiently incubating their eggs, while the males are seen regularly leaving the nests to retrieve food for their mates, or find bits of grass and twigs to strengthen their homes.

The males seem to leave in turns. Each time one departs, he makes a full circle around the whole colony, presumably scouting for danger, before leaving the aerie for his more mundane tasks.

Their flight, plumage and stature are elegant in the extreme. It is very calming to watch them, as their huge size creates the illusion that they are flying in slow motion.

As I watch them through binoculars, I feel like I am getting a glimpse into the graceful flight of ancient pterodactyls.

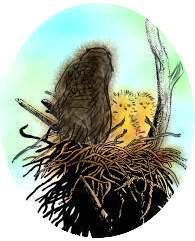

Having observed the couples nesting this way over a period of several springs, I realized that I had never seen the hatchlings. . . . ever. So, one spring I became obsessed with getting to see the baby herons and began visiting the aerie daily, intent on my objective. I was finally rewarded by the sight of two fat fluffy yellow chicks in a heron’s nest about midway down one of the trees in the center of the grove. I did not have my binoculars that day, but with the naked eye could see the silhouette of a large brown “parent” bird which looked like a heron with its back turned toward me, head down. In the nest next to her were what looked like two fuzzy yellow bowling pins.

I was very surprised by their fluffiness and found the size and coloring of the chicks very odd. I think I was expecting more of a gangly “plucked chicken” sort of appearance. I mulled this over all evening and decided to venture back the next day with binoculars.

Imagine my surprise when I discovered that what I thought was a mother heron sitting out on the limb by the nest, was in fact a great horned owl. These were owl chicks, not herons. I hurried home to do some research, discovering that owls do indeed like to take over the nests of herons and other large birds and they usually have two offspring that hatch much earlier in the season than most other birds.

I continued to return to the nesting site daily, but now with the aim of observing the habits of the owl family in mind. The changing life stages of the owlets became a delight to watch. First poking up from the safety of the nest, next venturing out onto a nearby limb and finally, no owlets to be seen anywhere near the nest.

Though disappointed in no longer being able to see the baby owls, I continued to walk in that same direction daily. One day I noticed on the path below my feet a few scat pellets. Upon closer observation of the small grey clumps, tiny rodent bones (probably a mouse or vole) were clearly visible. I looked directly above me, and there on a branch overhead were the two sibling owlets,

somewhat larger, still quite fuzzy, but now browner in color.

I scanned the nearby trees and was rewarded by the sight of the watchful mother, calmly sitting on a branch of a tree about a half of a football field away.

The owlets had graduated to the stage of being able to hunt for themselves, but were not yet wise enough to stay away from a low branch crossing a fairly heavily trafficked walking path. But that was okay. Mother was nearby, letting them stretch their wings, but keeping a watchful eye from a distance.

As for the baby herons, I came to realize that probably no one ever gets to see them, as they hatch much later in the season when the trees are in full foliage, thus hidden from prying eyes. Perhaps that’s just as well, because this is what they look like:

Definitely more of a scrawny chicken thing going on.

For another Springtime Story, Empty Nester please click “2”