One morning right after breakfast and the usual dismissals by his parents, Charles ran across the shiny expanse of the wide entry hall and straight out the front door to the garden, where old Cholly, the head caretaker, was shuffling across the lawn.

“Cholly, wait for me!” called Charles. “I’m coming to help you!”

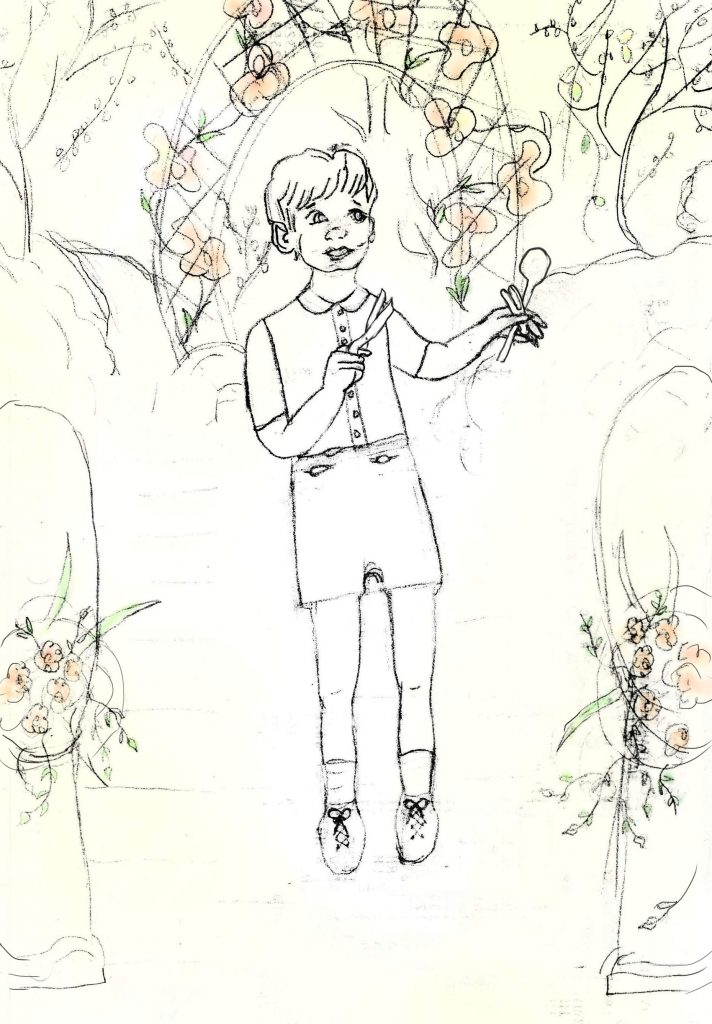

“See,” continued Charles, “I have my gardening tools. My pruning shears,” one hand clutching a hand-carved wooden scissors crafted by the adroit Jock, one of Cholly’s garden helpers, “…..and my hedge clippers!” the other hand holding a wooden clothespin, “….and my digging trowel!” This last was an old discarded cooking spoon from Mathilda’s kitchen.

“Not this morning, Master Charles. I’ve much to do. I must attend to the Royal Princesses, Glowing Sunlights and Velvet Crimsons….” Old Cholly rattled off another half dozen or so colorful names for his Mistress’s many varieties of roses. “There’d be the devil to pay young Master,” he continued. “He’s a jealous one, sending more plagues on your mother’s roses than all the Pharaohs of Egypt had to endure. I saw Mrs. Aphid and a dozen of her young’uns on the Velvet Whites this morning. I’ll have to do something about that, that’s all.” Humming softly, in his tuneless way, Cholly shuffled off in his lopsided, arthritic gait, forgetting Charles altogether, as if the boy had never been there at all.

Just a few years past, when Charles was still in his cradle, Cholly deemed the rose garden a frivolous, foolish and even wasteful venture. With so many more pressing duties involved in maintaining such a large estate he had no time for such “fripperies”. Then, when Charles’ father, now master of the estate, had hired more help, Cholly rebelled in silence and petulance, feeling cast aside and useless. In time, Cholly resigned himself to this new arrangement.

He was too contrary to admit it, but before long he came to love the rose garden the Master had started for his Lady. Now in Cholly’s senior years, it had become his pride, joy and sole occupation; really more of an avocation. The two extra hired hands, Jock and Germaine, had proven over time to be a godsend, handling the upkeep of the extensive grounds. Any heavy preliminary work done on the rose garden, such as expansion, was also taken on by these two strong, willing young helpers. Cholly had never been happier.

Cholly had been with Charles’ family for many years, first coming to the estate when just a lad. He had been brought there from Switzerland by Charles’ great-grandfather, who had visited the Alpine country while doing a Grande Tour of Europe with his young bride. Though small in stature at the time, Cholly grew to be a strong, muscular young man with seemingly limitless energies and capabilities. The stubborn, old country ways of his forefathers of “doing it all himself'” served him well, as he had grown into a veritable small Samson.

He still remembered his early years as a youngster in his native Switzerland. Fond memories of the sounds of his father calling cows in from the field to be milked in early evening still echoed in his heart. When the weather was extra fine and he felt unusually well, his father liked to yodel as he did the milking. Sometimes, on a Sunday afternoon, Cholly’s uncle from the city would come and visit them, to enjoy some time in the country. He would help Cholly’s dad with the evening milking and they would yodel in unison. When he was a lad, no bigger than Charles, Cholly enjoyed his uncle’s rare visits. He most enjoyed seeing how happy it made his father to have his brother’s company if even for only a day.

Sometimes in the early morning when alone, or with just Charles, on a particularly fine day Cholly would yodel, like his father had in the old country. His voice would carry a great distance in the clear, cool, crisp air and echo back to him from the surrounding hills. Charles loved the sound; it made him feel good too. He would try to mimic Cholly, but with his child’s voice, would fail dramatically. But Charles never ceased trying to join in, as Cholly always encouraged him and said that with practice, he would learn too.

Cholly had been the sole caretaker for his Master and Mistress’ estate for many years, doing all of the landscaping and tending of the grounds himself. He had not only maintained a vegetable garden and orchard, but pruned vines and shrubs and cared lovingly and patiently for the flower beds. But now the kindly old man was stooped with age, with rough calloused hands and gnarled fingers that were surprisingly gentle in working with the delicate roses. He had a big walrus-like mustache that matched the abundant white halo of hair around his pink bald pate. He spoke only sparingly in a heavy German accent, using broken English, resulting in a self-conscious demeanor of taciturn reticence. He more than made up for his mute shyness, though, with a sweet toothless smile that gave him an elfin charm.

On the rare occasions when moved to anger, Cholly could curse with the best of them. Under his large bush of a mustache, he would rail against uncooperative weather, a recalcitrant mule or his own physical inadequacies with a colorful vocabulary that could scorch one’s ears. But when the Angelus rang out three times a day, morning, midday and evening, from the distant church he attended every Sunday, he would stop, take cap in hand, bow his head and pray the familiar prayers he had learned as a boy. Then it was back to work again with a renewed vehemence.

This particular morning, while old Cholly was working with spade, mulch and compost on his Mistress’ flower beds, Charles busied himself with his own little makeshift tools at the far end of the garden, trying to stay out of Cholly’s way.

His joy of helping was of short duration, though, as every time the old gardener moved closer, Charles was obliged to distance himself still farther so as to “keep out from under foot!”

Frustrated with Cholly’s constant admonishments to “move along young man”, Charles soon grew weary of his attempts at gardening and decided to turn his attentions elsewhere.

. . .continue to Chapter III: Andrews